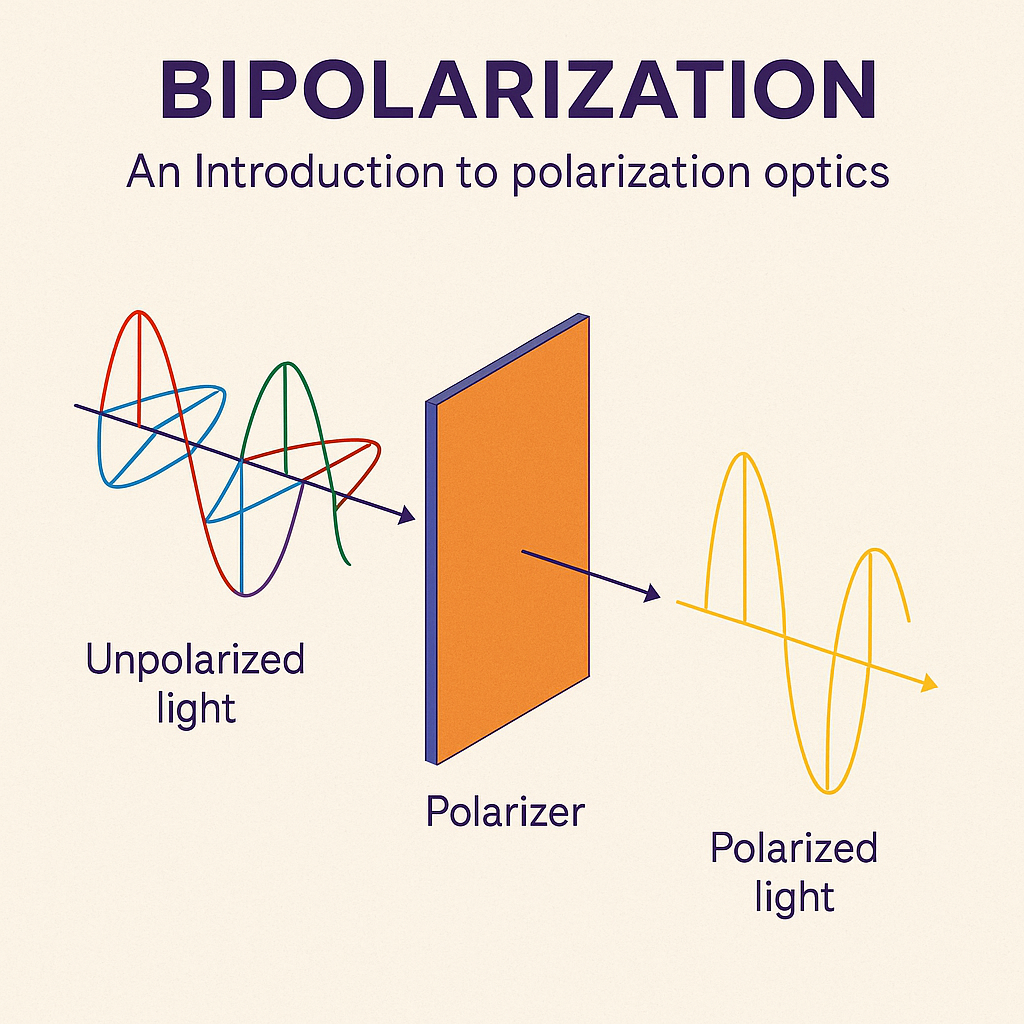

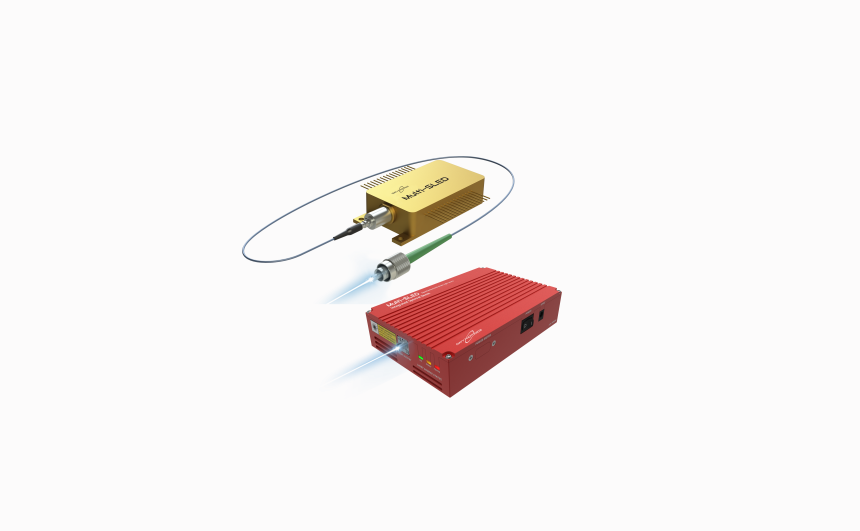

When working with lasers and sensitive optical systems, it's sometimes crucial to prevent light from reflecting back into the system. In lasers, for example, light reflected into the resonator cavity can disrupt its operation, cause instability, or even damage the laser. To avoid this, we need an optical isolator - a component that lets light travel in one direction but blocks it in the opposite direction.

The challenge is that most optical systems obey a principle called reciprocity. If a beam of light can travel in one direction, it can also return along the same path. “If I can see you, you can see me.” Components like polarizers and waveplates are symmetric - they can modify the polarization of light, but they can’t prevent it from traveling in the reverse direction. To break this symmetry, we need something different - something that behaves differently in the forward and backward directions.

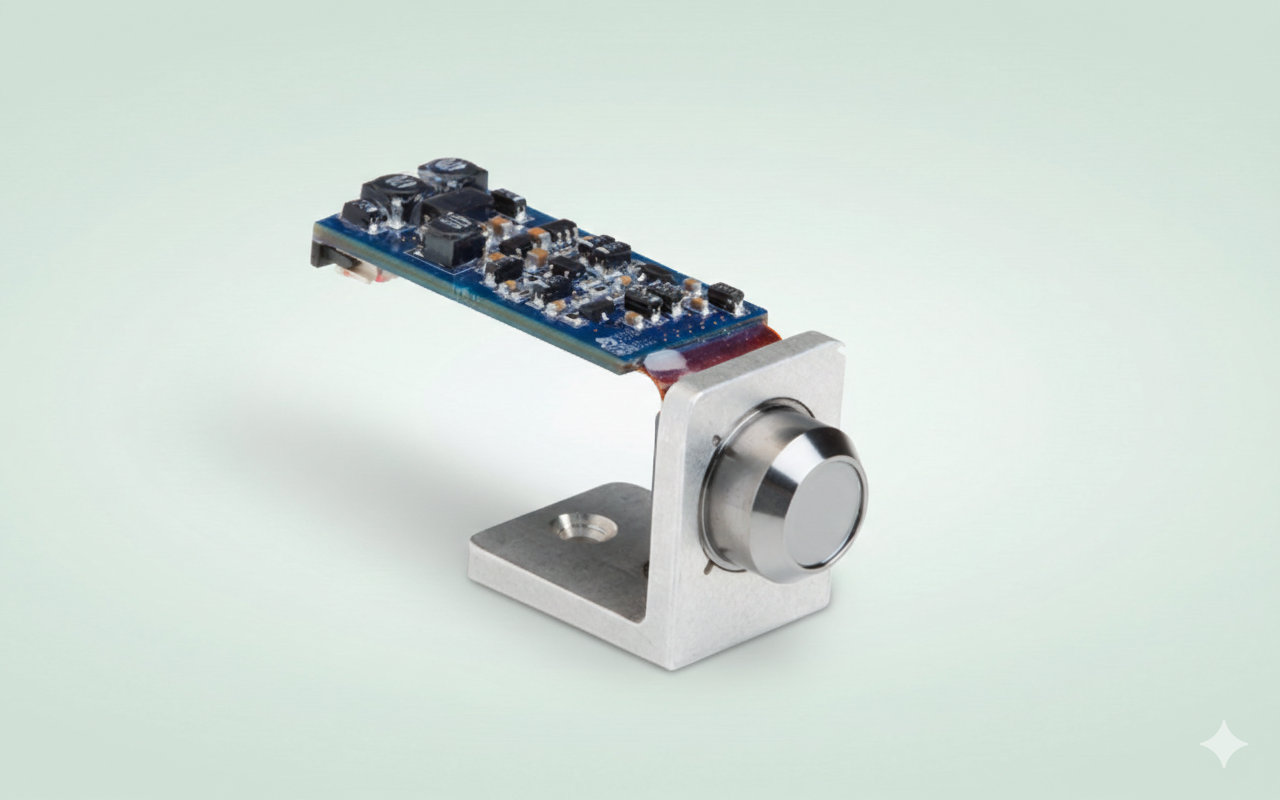

One of the most common solutions is based on the Faraday effect, a magneto-optical phenomenon that occurs when light passes through a material under a magnetic field. In such a material, the polarization direction rotates as the light travels through, but unlike a waveplate, the rotation always occurs in the same direction, regardless of the light’s propagation direction. Michael Faraday discovered this effect in 1845, and it served as the first experimental proof of a direct link between light and electromagnetism - a discovery that ultimately led to Maxwell’s unified theory of electromagnetism.

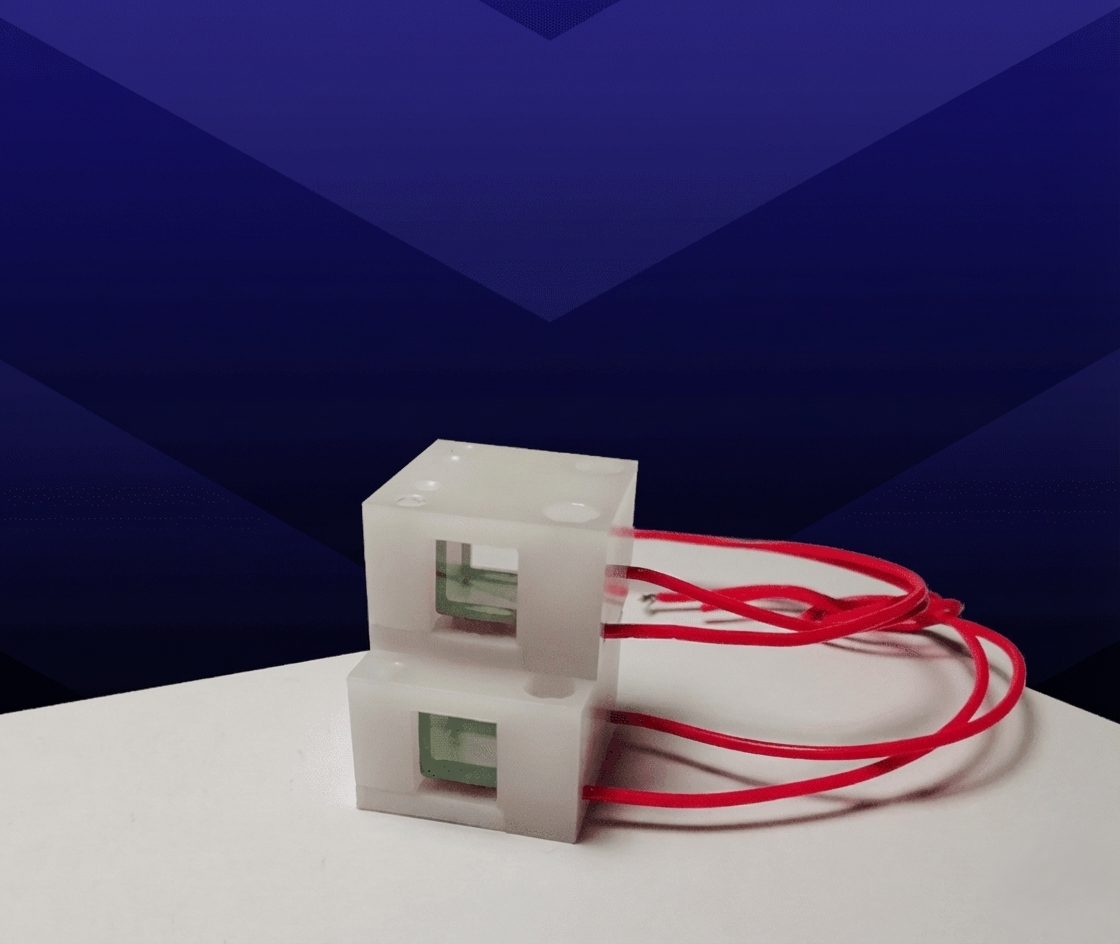

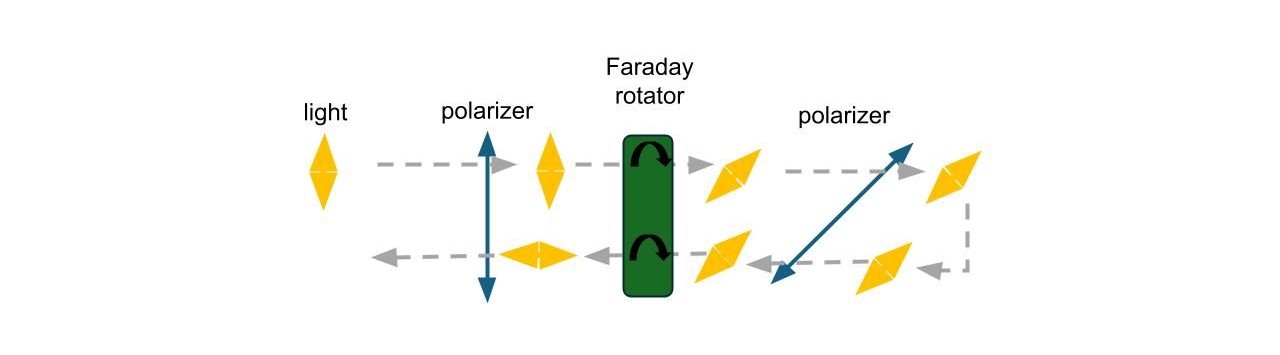

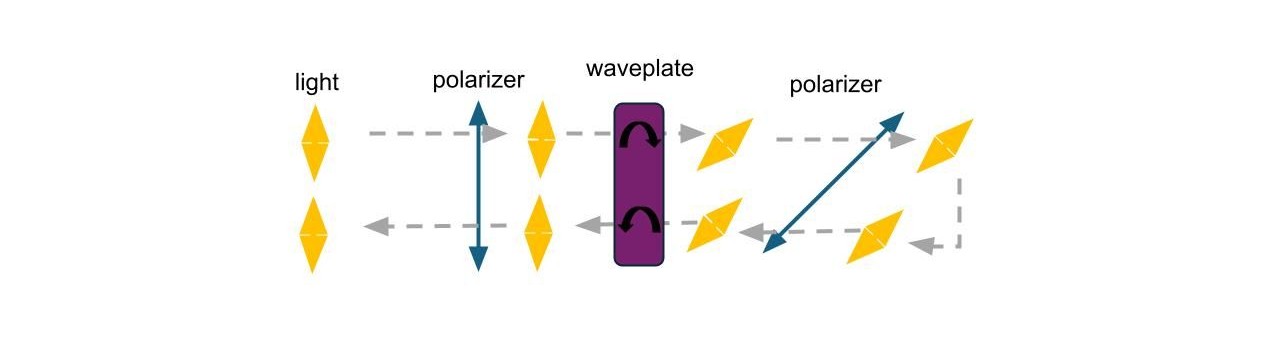

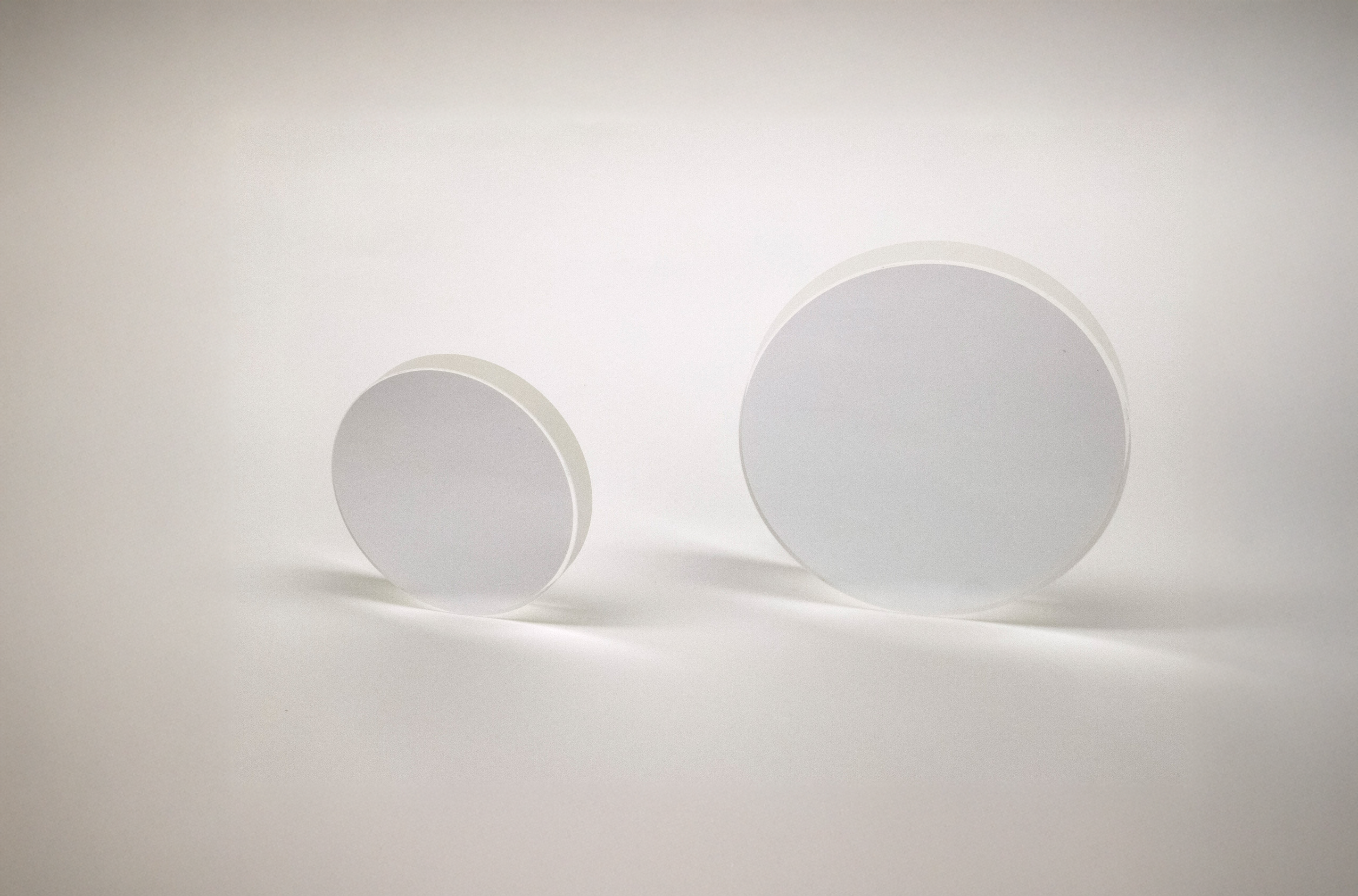

To use this effect in an optical isolator, we place one polarizer before the material and a second polarizer after it, rotated 45 degrees relative to the first. In the forward direction, the Faraday effect rotates the polarization just enough to match the second polarizer, allowing the light to pass. But if the light tries to go backward, it rotates again in the same direction, ending up perpendicular to the first polarizer, so it gets blocked (see image below).

At first glance, you might think a waveplate could do the same thing, since it can also rotate polarization by 45 degrees! But here reciprocity gets in the way - a waveplate always rotates polarization symmetrically, so if light passes in one direction, it will pass the same way in reverse. That’s why a one-way valve can't be built using a waveplate alone (see image below). Without the non-reciprocal behavior provided by the Faraday effect, it simply won't work!

In the next article, we’ll conclude our polarization series with a fascinating experiment - where we help light pass... by blocking it! What other topics would you like to hear about? Let us know!

.jpg)

.png)